No Man’s Land, Project 2012—2014

[Terra de Ninguém/No Man’s Land 2012 — Core of the Project, Le Boudin 2014]

No Man’s Land, Project (2012–2014) comprises the films No Man's Land (2012) — core of the project and Le Boudin (2014)

In No Man’s Land, the protagonists of the two films were combatants and mercenaries whose personal accounts defy imagination. The stories told are linked to Portugal, Spain, and France, with special attention to the countries’ criminal and correctional systems and to the inability of democracies to enforce their own ideals.

The project was self-initiated.

TERRA DE NINGUÉM / NO MAN’S LAND (2012)

HD video, 16:9, color, stereo sound, 72 min., Portugal

Production: O Som e a Fúria

Additional support: Carpe Diem, Bikini, Óbvio Som, Galeria Miguel Nabinho

Support: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

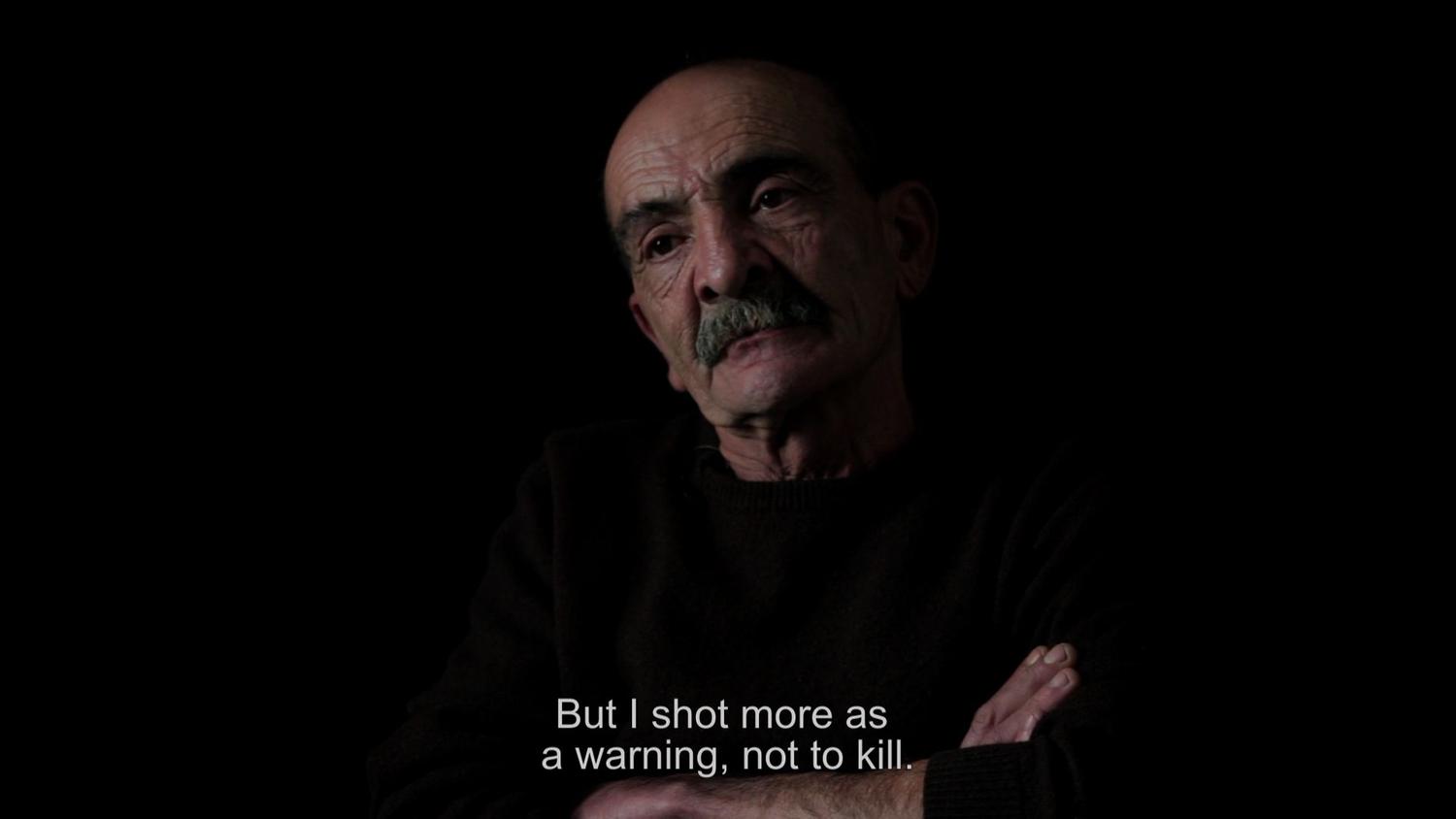

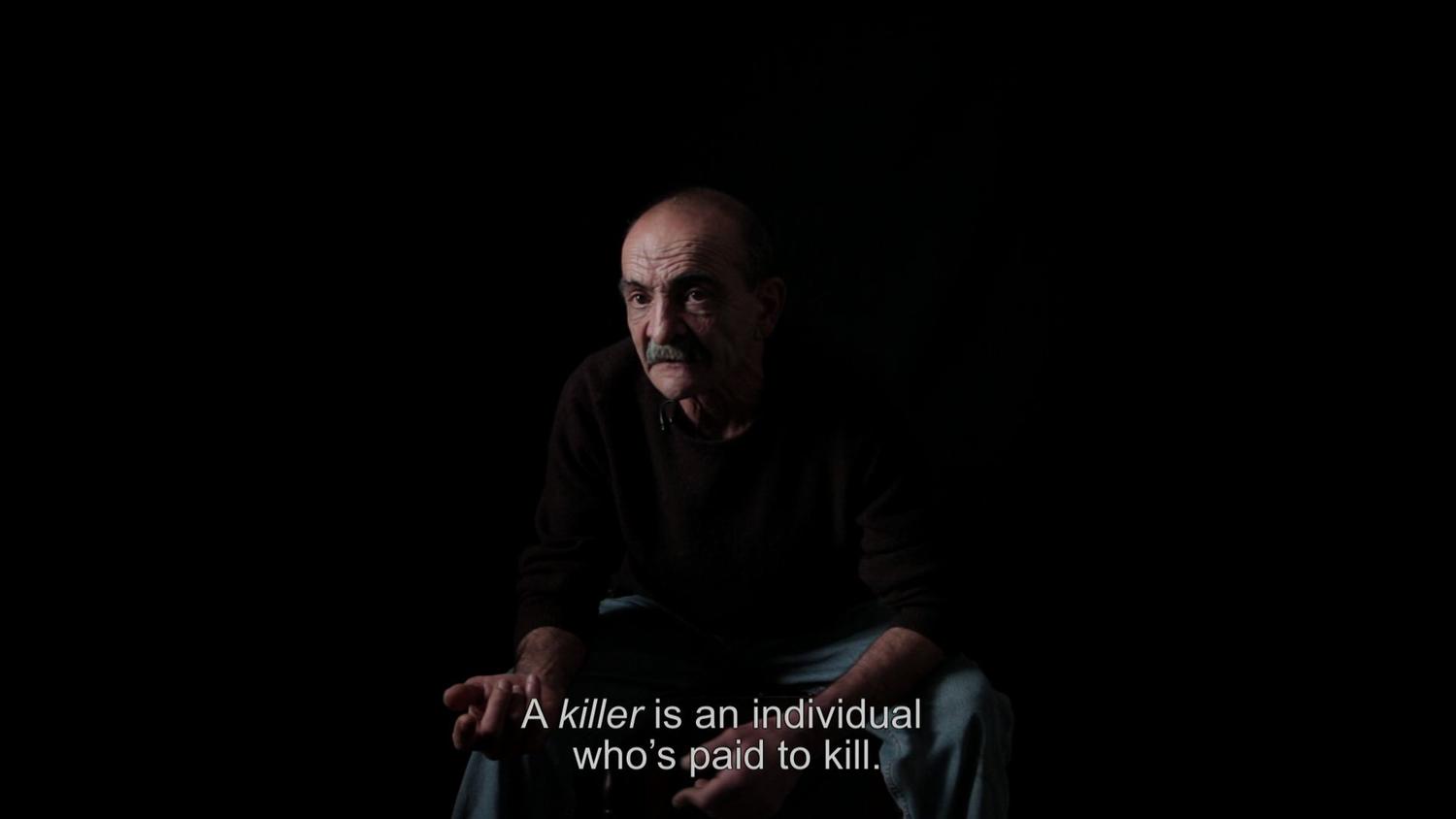

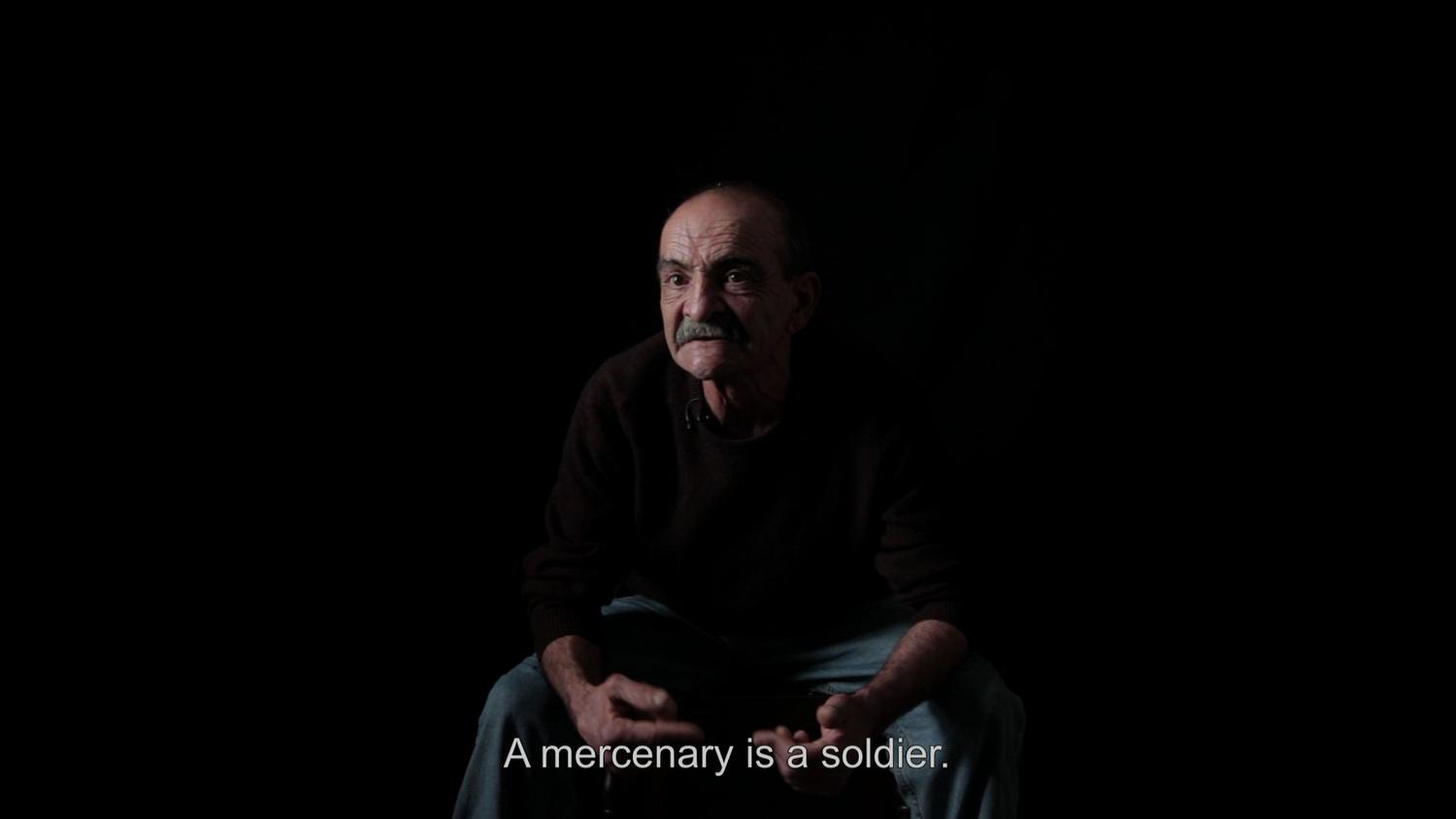

A mercenary sits in silence on a chair placed in an abandoned palace in Lisbon, as if posing for a portrait. Facing the camera, he begins narrating and performing his own history, constructing a record which slowly reveals, in its turns of phrase and mismatched events, a series of doubts and contradictions. The camera watches, relentlessly. Paulo describes his involvement as a hired killer for special military forces during the Portuguese colonial war, the part he played in the GAL (Antiterrorist Liberation Group), a death squad illegally established by the Spanish government to annihilate high officials of ETA, and his work as a mercenary for the CIA in El Salvador.

Rather than affirming or discrediting the veracity of the historical record, or proving or disproving an official narrative, No Man’s Land dwells in the present moment of witnessing—the space inhabited by the performance of a memory. Refusing to linger on a static moral duality, throughout the film, the accuser and the accused are frequently asked to change positions. At a certain point, after describing a series of crimes he committed, responding to a question by the director, Paulo replies with one of his own: 'How much is a man's life worth? A man like me or men like them?' As the film’s own processes of making are slowly revealed, No Man’s Land creates a set, a stage, where information and documentation are peripheral to the question of how one plays out and affirms as history one’s own personal truth.

Paulo offers sublime portrayals of the cruelties and paradoxes of power and of the revolutions that brought it down, only to erect new bureaucracies, new cruelties, and paradoxes. His work as a mercenary is on the fringe of these two worlds.

The documentary avant-garde today seems focused on perpetrators rather than victims. One of the most compelling and controversial of such films comes from filmmaker Salomé Lamas, who offers us one of cinema’s most arresting subjects in her brilliantly imagined, starkly powerful cinematic work. Terra de Ninguém (No Man’s Land) brings us face-to- face, it seems, with a classically unreliable witness, a man in his sixties who is charming, engaging, and terrifying all at once.[…]

But what holds us forcefully throughout this 72-minute testi- mony is not just his larger-than-life personality but Lamas’ filmmaking. She is a master stylist working with a brilliant cinematographer (Takashi Sugimoto). Within a minimalist set atmospherically lit to evoke both an illicit inter- rogation chamber and the shadowy recesses of a disturbed self, Lamas stages the interview to elicit our curiosity about Figuereido and our attraction-repulsion to him and his story. The details of his exploits are appalling and often sordid, but his skill at storytelling and her skill as off-screen interrogator hold us fast like prey caught in a predator’s grasp.

[…]

This is a film that will leave you thinking about colonialism and its abusive aftermath, about the personal sources of violence and aggression that can be tapped by political powers around the globe, about the foot sol- diers who enthusiastically wage clandestine wars, hidden and invisible. It is also about madness and sociopathy and the thin line di- viding heros from villains. It is a film that brings us to the brink to see ourselves in people we may not want to know yet cannot stop con- templating. Whether Paulo is who he claims to be or not, he embodies the banality of evil in the modern world and offers us much to con- sider about him and about ourselves.

Deirdre Boyle, Warrior to warrior: Salomé Lamas’s Terra De Ninguém

[…] a work of unusual maturity, raising questions about the relation-ship of memory with history, contributing to the acknowledgment of a human being in his complexity. Without being a historical investigation–and very less a trial–for the lack of documents/sources that prove and contex- tualize what Paulo relates, the film is a beau- tiful narrative of the life of a Portuguese man, a commando, a mercenary, a hired assassin, and a homeless man. All of that, a bit of everything or nothing at all, for no human being can be restrained by a single definition. Paulo existed, hence the need for him to be filmed. Thanks to Salomé Lamas for placing herself in the position of another, despite how repug- nant his life may have been, to not judge, nor forgive, but open a sliver of opportunity to understand how this man was possible.

Irene Flunser Pimentel, The truth or the lie in Terra De Ninguém a film by Salomé Lamas

The documentary avant-garde today seems focused on perpetrators rather than victims. One of the most compelling and controversial of such films comes from filmmaker Salomé Lamas, who offers us one of cinema’s most arresting subjects in her brilliantly imagined, starkly powerful cinematic work. Terra de Ninguém (No Man’s Land) brings us face-to- face, it seems, with a classically unreliable witness, a man in his sixties who is charming, engaging, and terrifying all at once.[…]

But what holds us forcefully throughout this 72-minute testi- mony is not just his larger-than-life personality but Lamas’ filmmaking. She is a master stylist working with a brilliant cinematographer (Takashi Sugimoto). Within a minimalist set atmospherically lit to evoke both an illicit inter- rogation chamber and the shadowy recesses of a disturbed self, Lamas stages the interview to elicit our curiosity about Figuereido and our attraction-repulsion to him and his story. The details of his exploits are appalling and often sordid, but his skill at storytelling and her skill as off-screen interrogator hold us fast like prey caught in a predator’s grasp.

[…]

This is a film that will leave you thinking about colonialism and its abusive aftermath, about the personal sources of violence and aggression that can be tapped by political powers around the globe, about the foot sol- diers who enthusiastically wage clandestine wars, hidden and invisible. It is also about madness and sociopathy and the thin line di- viding heros from villains. It is a film that brings us to the brink to see ourselves in people we may not want to know yet cannot stop con- templating. Whether Paulo is who he claims to be or not, he embodies the banality of evil in the modern world and offers us much to con- sider about him and about ourselves.

Deirdre Boyle, Warrior to warrior: Salomé Lamas’s Terra De Ninguém

Deirdre Boyle, Warrior to warrior: Salomé Lamas’s Terra De Ninguém

[…] a work of unusual maturity, raising questions about the relation-ship of memory with history, contributing to the acknowledgment of a human being in his complexity. Without being a historical investigation–and very less a trial–for the lack of documents/sources that prove and contex- tualize what Paulo relates, the film is a beau- tiful narrative of the life of a Portuguese man, a commando, a mercenary, a hired assassin, and a homeless man. All of that, a bit of everything or nothing at all, for no human being can be restrained by a single definition. Paulo existed, hence the need for him to be filmed. Thanks to Salomé Lamas for placing herself in the position of another, despite how repug- nant his life may have been, to not judge, nor forgive, but open a sliver of opportunity to understand how this man was possible.

Irene Flunser Pimentel, The truth or the lie in Terra De Ninguém a film by Salomé Lamas

Irene Flunser Pimentel, The truth or the lie in Terra De Ninguém a film by Salomé Lamas