Extinction, Project 2015–2018

[A Torre/The Tower 2015, Autorretrato/Self-Portrait 2017-2018, Horizon Noziroh 2017, Extinction 2018 — Core of the Project, Dream World 2018]

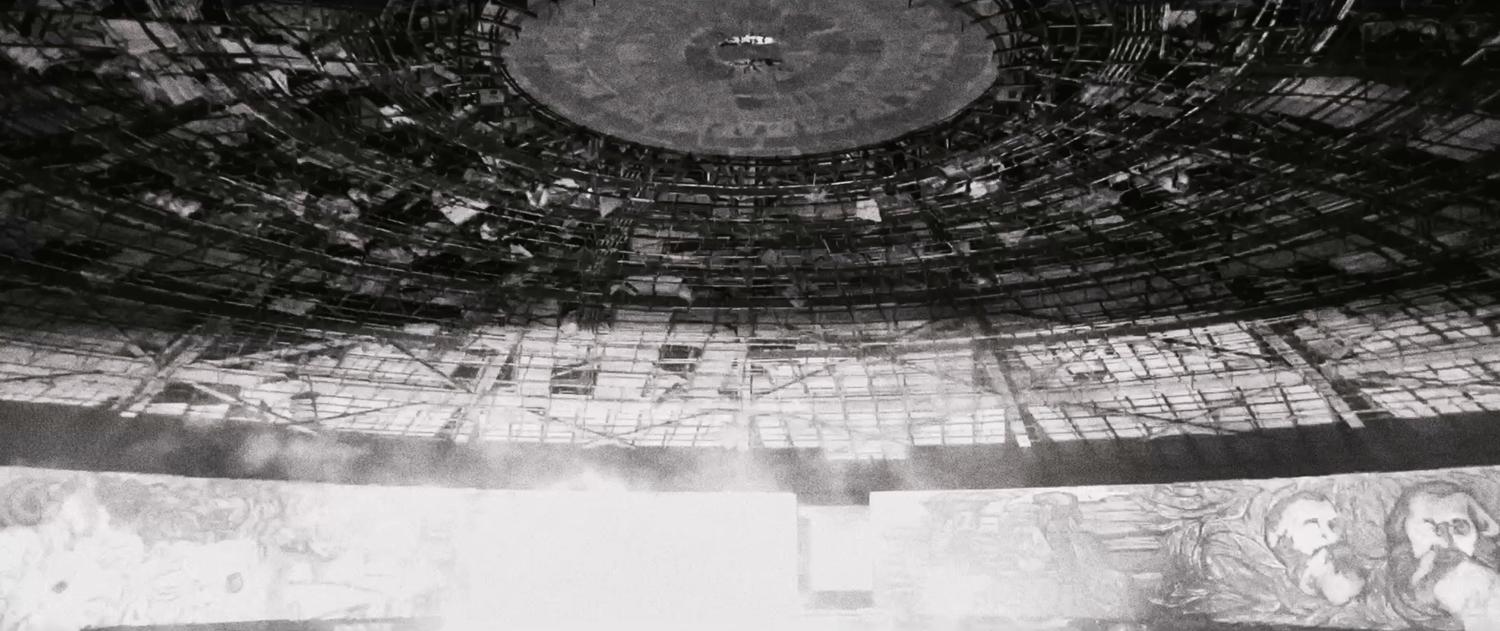

Extinction, Project (2015–2018), comprises A Torre / The Tower (2015), the photogravures Autorretrato / Self-Portrait (2017–2018), the installation Horizon Noziroh (2017), the film Extinction (2018) — core of the project, the film Self-Portrait (2018), and the photographs Dream World (2018). Extinction, in a political limbo, takes a stand to question Eastern European narratives, entrenched in a polarity of communism and post-communism, but which are much more complex than that, finding their loudest expression in the divorce of politics from life.

The project was self-initiated. The other productions were developed due to other partners and exhibited accordingly.

CPH: DOX

Escola das Artes – Universidade Católica Portuguesa

Solar – Galeria de Arte Cinemática

Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

Curtas Metragens CRL

EXTINÇÃO / EXTINCTION (2018)

HD video, 2:39, black and white, Dolby 5.1 sound, 80 min., Germany/Portugal

Production: O Som e a Fúria, Lamaland

Coproduction: Mengamuk Films

Associate production: Walla Collective, Screen, Bikini

Selected: Agora Works in Progress 2016 Thessaloniki

Additional Support: Screen, Walla Collective, Bikini, Yuki, Bogliasco Foundation, Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio,, Yaddo

Support: ICA – Instituto do Cinema e do Audiovisual, Berlinar Kunstlerprogramm des DAAD, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

I don’t have an easy relationship with borders. They frighten and unnerve me. I have been searched, prodded, delayed, again and again, for having the temerity to cross a few meters of land. Borders are bureaucratic fault lines, imperious and unfriendly. Their existence is routinely critiqued by academic geographers, who cast them as hostile acts of exclusion. And yet, where, in a borderless world, could we escape to? Where would it be worth going?

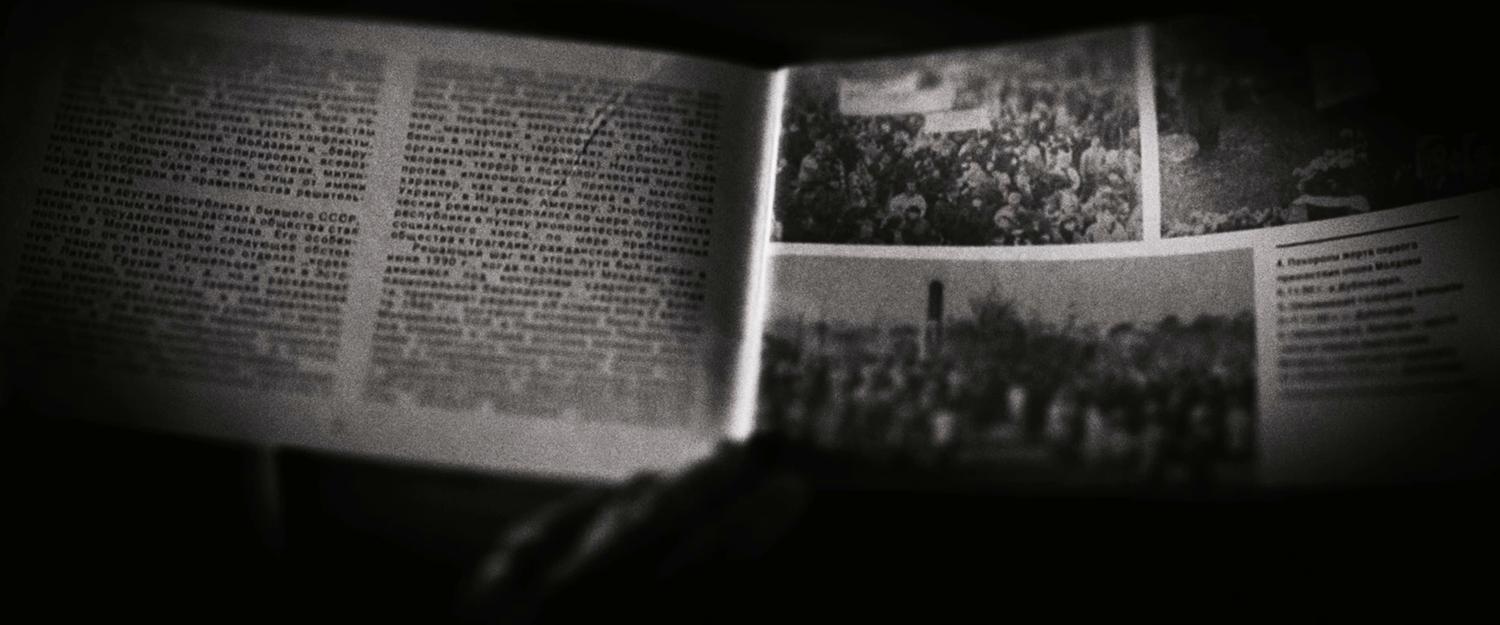

The end of the Cold War did not produce a thaw throughout the continent. A peculiarity of today's Europe is the variety of ‘frozen conflicts’ it contains. Transnistria is an unrecognized state that broke away from the former Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union in 1990.

Lamas’ modes of production are somehow attracted to “nowhere-ness” or the unknown, to characters that may be deemed as marginal in the eyes of many. Here it may be appreciated how we go back to the concept of margins. And how this becomes a trait d’union between the philosophical and political structure of Lamas cinema and her subsequent and connected approach to film production.

[…] Salomé’s work is often interrogated if suitable more for gallery space environments or cinema rooms, there is little doubt I think how we as viewers and spectators we can best concentrate on the work and take advantage of the best possible sound conditions from a theatrical presentation. However, the sense of immediacy and personal connection to the work offered by a space like the one where this museum is showing Extinction, it’s hard to intercept in a theatrical setting. (…) The memory of the maker, the memory of the film subjects and the collective memory triggered by the work itself. This specific and multiple approach of elements comes back in Lamas heterogenous works to create a very particular style, where the accuracy and the beauty of images meet a minimalist treatment of them. (…) Reproduction of history as an exercise that allows an active spectator. Lamas attempts at emptying the frame as much as possible. Using the image to step away from the image itself, to provide a cinematic experience that may help us in recollecting to address questions such as how do we remember? How do we tell our stories to ourselves and to those around us? Nico Marzano, Notes for the parallel program of the solo exhibition Extinc(ão) at MNAC.

Nico Marzano, Notes for the parallel program of the solo exhibition Extinc(ão) at MNAC

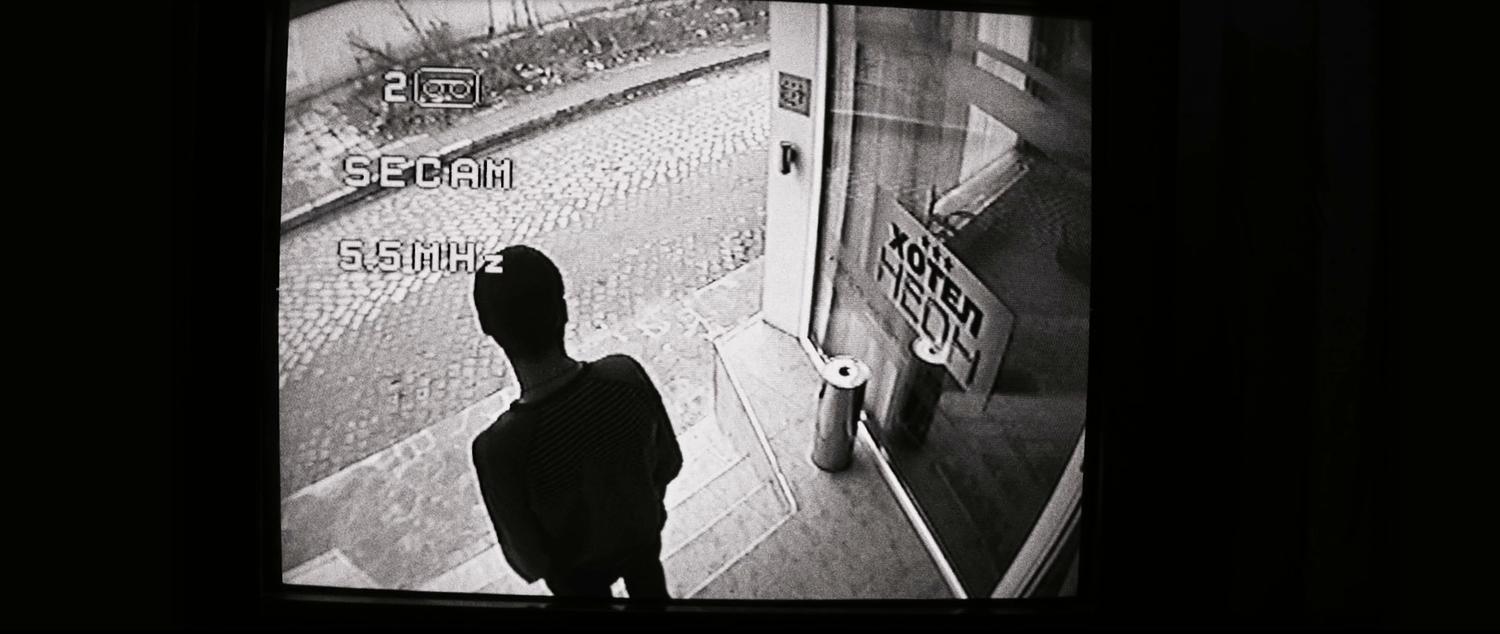

In black, white, and smoky gray, a young man stares back at us in slow motion. That same man sits in the back of a car as it hurtles down wet streets, then wanders around desolate landscapes, conversing with various strangers about the collapse of the Soviet Union and the splintering that followed. Yet no matter how arresting these images are, the most important activities in Extinction aren’t visually depicted.

[…] You’re drawn to the frame and also past it, replacing a lack of projected imagery with your own private projections of what’s missing. Private in that they’re invisible to others and subjective in detail, prompted and motivated by what’s objectively present and richly suggestive: the soundtrack. (…) Here sound doesn’t merely fill in what’s absent, it challenges and converses with a screen that answers back with pointed opacity. Meanwhile the viewer, while ideally always engaged, has no choice but to actively process and synthesize, to get to work.

Eric Hynes, Film Comment, May/June 2018 Issue

The poetics of space may be considered one of the main conceptual dimensions in the work of Salomé Lamas, especially as regards this film. Lamas’s work is particularly hard to catalog because it cannot readily be boxed into any one specific category of audiovisual language. Perhaps it might be considered a form of parafiction, in that it is situated in the realm of creative non-fiction, in which, as the author herself says, “concepts such as credibility and perception have taken the place of objective truth”, giving rise to a “politics of simulation” that she calls by that term, “parafiction” (Lamas, 2019). This parafiction operates as follows:

The starting point I take [in my work] is simple and childish. I choose a limited reality and relocate it. This is a point of no return. I wait. I wait until the presence in my strange body and the other’s experience in me generate a friction until the ordinary becomes extraordinary. I wait patiently. Sometimes the movement of my process of initial relocation (or restitution) is enough, sometimes it is not, and I have to readjust the distance. It is an exercise in distance, duration, and occupation (Lamas, 2019: 12).

[…]

Lamas’s film materializes the political paradoxes this territory faces by using a form of filmmaking that deliberately stands on the sidelines of what is representable and, because of its very nature, becomes paradoxical. What is absent, out of field, is precisely what makes it possible to articulate a poetics of impossibility, what gives visibility to a corrupted Soviet utopia, and what permits the image to show us that, indeed, “there is no there there”.

Alba Giménez Gil, “There is no there there”: Extinção and the unrepresentable space

Lamas’ modes of production are somehow attracted to “nowhere-ness” or the unknown, to characters that may be deemed as marginal in the eyes of many. Here it may be appreciated how we go back to the concept of margins. And how this becomes a trait d’union between the philosophical and political structure of Lamas cinema and her subsequent and connected approach to film production.

[…] Salomé’s work is often interrogated if suitable more for gallery space environments or cinema rooms, there is little doubt I think how we as viewers and spectators we can best concentrate on the work and take advantage of the best possible sound conditions from a theatrical presentation. However, the sense of immediacy and personal connection to the work offered by a space like the one where this museum is showing Extinction, it’s hard to intercept in a theatrical setting. (…) The memory of the maker, the memory of the film subjects and the collective memory triggered by the work itself. This specific and multiple approach of elements comes back in Lamas heterogenous works to create a very particular style, where the accuracy and the beauty of images meet a minimalist treatment of them. (…) Reproduction of history as an exercise that allows an active spectator. Lamas attempts at emptying the frame as much as possible. Using the image to step away from the image itself, to provide a cinematic experience that may help us in recollecting to address questions such as how do we remember? How do we tell our stories to ourselves and to those around us? Nico Marzano, Notes for the parallel program of the solo exhibition Extinc(ão) at MNAC.

Nico Marzano, Notes for the parallel program of the solo exhibition Extinc(ão) at MNAC

Nico Marzano, Notes for the parallel program of the solo exhibition Extinc(ão) at MNAC

In black, white, and smoky gray, a young man stares back at us in slow motion. That same man sits in the back of a car as it hurtles down wet streets, then wanders around desolate landscapes, conversing with various strangers about the collapse of the Soviet Union and the splintering that followed. Yet no matter how arresting these images are, the most important activities in Extinction aren’t visually depicted.

[…] You’re drawn to the frame and also past it, replacing a lack of projected imagery with your own private projections of what’s missing. Private in that they’re invisible to others and subjective in detail, prompted and motivated by what’s objectively present and richly suggestive: the soundtrack. (…) Here sound doesn’t merely fill in what’s absent, it challenges and converses with a screen that answers back with pointed opacity. Meanwhile the viewer, while ideally always engaged, has no choice but to actively process and synthesize, to get to work.

Eric Hynes, Film Comment, May/June 2018 Issue

Eric Hynes, Film Comment, May/June 2018 Issue

The poetics of space may be considered one of the main conceptual dimensions in the work of Salomé Lamas, especially as regards this film. Lamas’s work is particularly hard to catalog because it cannot readily be boxed into any one specific category of audiovisual language. Perhaps it might be considered a form of parafiction, in that it is situated in the realm of creative non-fiction, in which, as the author herself says, “concepts such as credibility and perception have taken the place of objective truth”, giving rise to a “politics of simulation” that she calls by that term, “parafiction” (Lamas, 2019). This parafiction operates as follows:

The starting point I take [in my work] is simple and childish. I choose a limited reality and relocate it. This is a point of no return. I wait. I wait until the presence in my strange body and the other’s experience in me generate a friction until the ordinary becomes extraordinary. I wait patiently. Sometimes the movement of my process of initial relocation (or restitution) is enough, sometimes it is not, and I have to readjust the distance. It is an exercise in distance, duration, and occupation (Lamas, 2019: 12).

[…]

Lamas’s film materializes the political paradoxes this territory faces by using a form of filmmaking that deliberately stands on the sidelines of what is representable and, because of its very nature, becomes paradoxical. What is absent, out of field, is precisely what makes it possible to articulate a poetics of impossibility, what gives visibility to a corrupted Soviet utopia, and what permits the image to show us that, indeed, “there is no there there”.

Alba Giménez Gil, “There is no there there”: Extinção and the unrepresentable space

Alba Giménez Gil, “There is no there there”: Extinção and the unrepresentable space